Last of Punakha

Before we left Punakha, we hiked up to see the Khamsum Yulley Namgyal Chorten. The terraced fields were stunning, and the monument itself is an impressive four-story affair, with a rooftop deck looking out over the surrounding area. It was built by the Queen Mother to help her son defeat any potential obstacles that he faces. Inside the monument, there are many paintings and statues of the wrathful god Vajrakilaya. This is a protector god who is usually depicted with three heads, six arms, and four legs. In two of his arms, he is holding a vajra, which is a Buddhist ritual object that represents a thunderbolt. (The Divine Madman, you might recall, named his phallus the Thunderbolt of Flaming Wisdom.) There are a lot of deities in Buddhism, and this is one of the gods I think I can now actually identify in a painting.

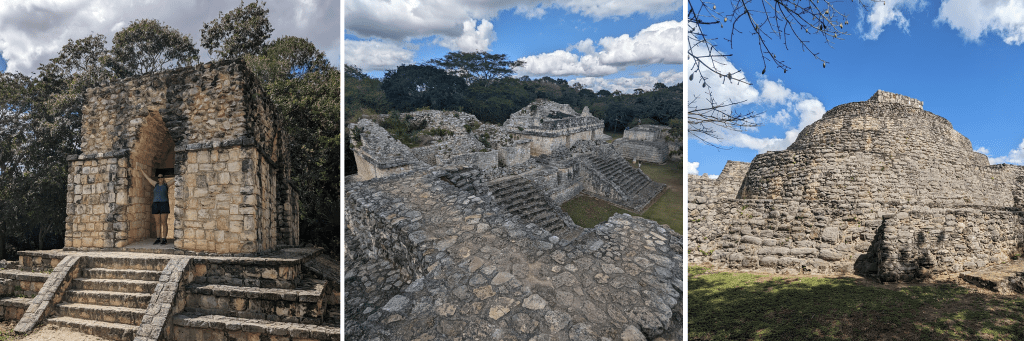

terraced fields of different crops, chorten, rows of stupas on surrounding wall

On the drive from eastern Bhutan, we started taking jumping photos with our guides. The first one was in front of a large monument, but then we took some on a bridge next to the Trongsa Dzong. Slowly, it became a ritual to take jumping photos whenever we found a bridge. Obviously, when we walked over the longest suspension bridge in Bhutan, we had to take some photos. We were pretty proud of these because it looks like we jumped way higher than we actually did.

Tenzin and me, Angela & Aja Pema

Onwards to Thimphu

The capital city of Thimphu looks and feels completely different than the rest of Bhutan. It was built in a meandering river valley, surrounded by hilly terrain. Unlike the quaint houses in small towns, Thimphu is full of government-subsidized multi-storied apartment complexes. Thimphu is the center of commerce and where most jobs are located. Many people who grew up in rural areas move into Thimphu to make more money than they can in their village. There are also a substantial number of Bhutanese moving abroad for educational and career opportunities. Many go to university in India or Australia and find ways to live overseas and send money home. Brain drain, the massive outward flow of educated citizens to other countries, is a real issue for modern Bhutan.

view of Thimphu driving into the city

I think one of the first times I ever heard about Bhutan was when the fourth king introduced the concept of measuring progress through Gross National Happiness. Basically, the idea is that non-economic aspects of life are as important as economic impacts (sometimes measured in Gross Domestic Product). The Gross National Happiness Index was developed to look at these other nine domains: psychological well-being, health, education, time use, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards. Each of these domains has specific indicators and citizens are polled on their responses.

The fourth king brought the idea of Gross National Happiness to the United Nations and because of his work, the United Nations now produces an annual World Happiness Report. The Bhutanese version includes items specific to Bhutanese culture, including spiritual measures such as meditation and prayer. The UN version leaves much of this out, but basically asks people to answer how happy they are on a scale of 1-10. There is much discussion about whether there are better ways to determine happiness. However, using these metrics, Finland has been rated the world’s happiest country for several years. Out of 150+ countries, Bhutan usually ends up somewhere in the 90’s.

According to this one survey, Bhutan may not be the world’s happiest country. However, on their own index, they do continue to see positive progress from year to year, even after the pandemic. The fourth king was also responsible for overseeing the introduction of democracy. The king still serves as head of state, but in 2008, the new constitution established an elected Parliament. The country is slowly changing and opening up to outsiders and business, but the idea is to do this at a pace that allows the country to hold on to its identity and culture.

Thimphu is the center of all this change, where new and old come together. In spite of being the most populous city in Bhutan, there are still no traffic lights. At the busiest intersection in the city, a policeman directs the flow of traffic. Apparently a few were installed in 1995 but drivers ignored them, so they were removed after 24 hours.

The capital city is also home to a takin preserve. Takins are Bhutan’s national animal. The local story is that they were created by the Divine Madmen when locals asked him to perform a miracle in front of them. He said he would if he was given a whole cow and a whole goat for lunch. He devoured both of them, leaving only the bones. He then took the skull of the goat and attached it to the rest of the cow’s skeleton and then brought this creature to life. In case you’re wondering, mitochondrial DNA suggests they are closely related to mountain goats.

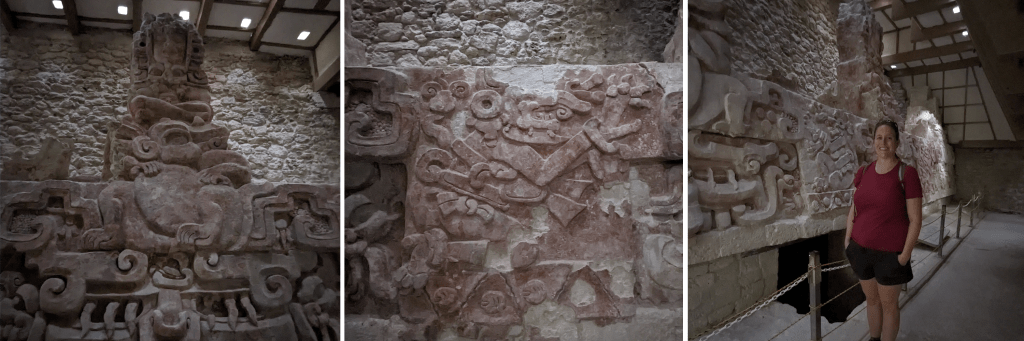

takin, biggest Buddha statue in Bhutan, cop directing traffic in Thimphu

Thimphu is also home to one of the first monasteries established by Zhabdrung Rinpoche, the man responsible for uniting the eastern and western parts of Bhutan. He set up the Bhutanese government system of having both a spiritual leader (Je Khenpo) who runs the monasteries and an administrative leader (Druk Desi) who runs the government. Cheri Monastery was built into the side of a hill and it’s a pretty steep climb to the top. It recently went through a picturesque renovation, with new decorations both outside and inside.

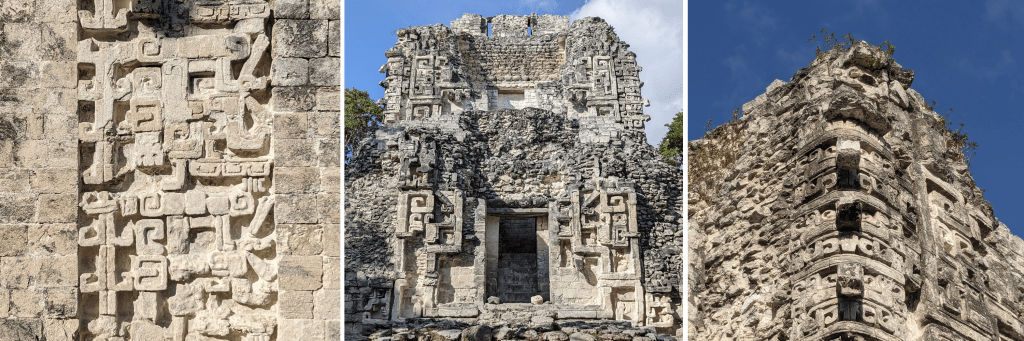

view of Cheri Monastery, temple roof (notice the garudas on the four corners), Angela and her new friend

At the start of the hike there is a bridge. Of course, we took more jumping photos.

bridge jumps – me, Tenzin, Angela & Aja Pema

This bridge crosses the Thimphu River and there is a sign at this spot that recalls a local story. Apparently an enlightened master had seven children with his consort. In order to test the dharma of his children, he threw them into the river. Only four of them survived and were considered worthy to continue living. Regardless of that gruesome story, the view off the bridge was jaw-droppingly gorgeous. This is probably one of my favorite photos that I took in all of Bhutan.