Valladolid

This town gets overlooked as a destination because most folks see it as the place to stay before and after a trip to Chichén Itzá. However, I thought it was a nice town to hang out in for a couple days even without the allure of the big Mayan ruins close by. In fact, I ended up visiting twice, once on my way to Mérida and once after my three weeks of Spanish school. The town is super walkable, there’s quite a bit of art in town, a cenote to jump in right in the center of town, and the food options were fantastic.

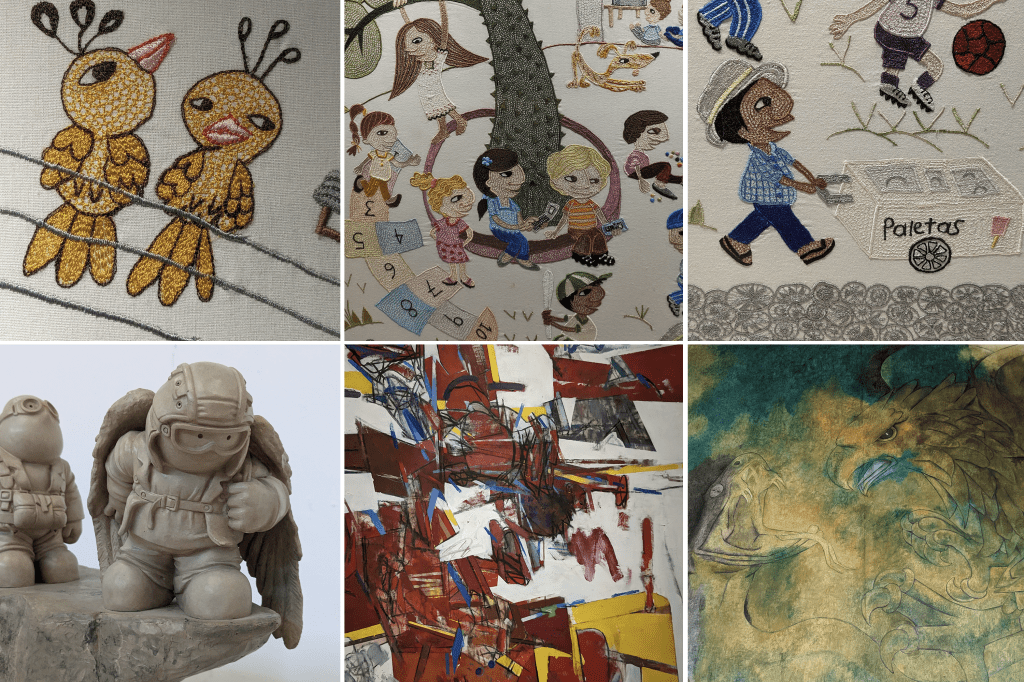

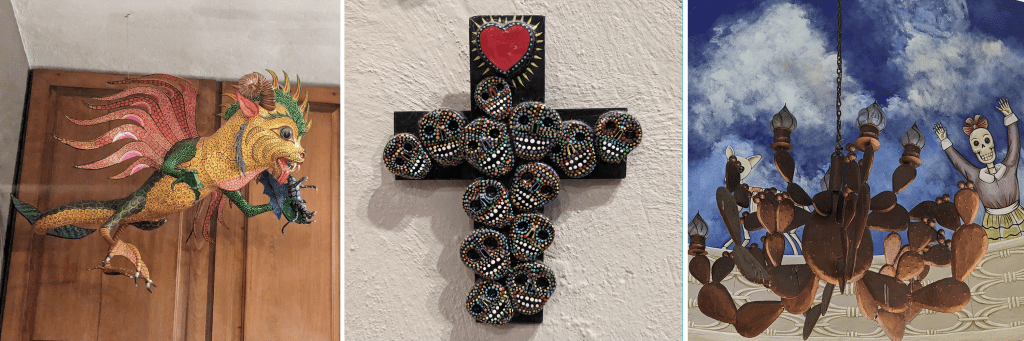

One of the local attractions is the Casa de los Venados, a private house owned by an American couple full of their personal collection of Mexican art. The wife passed away a few years ago, but the husband still lives there. They don’t charge anything for the tour, but take donations that are given to local organizations. There’s a wide variety of art, including a fancy dining room set complete with portraits of famous Mexicans on the back of the chairs and a shaman costume and mask that apparently decorated with real animal blood.

artwork from the Casa de los Venados

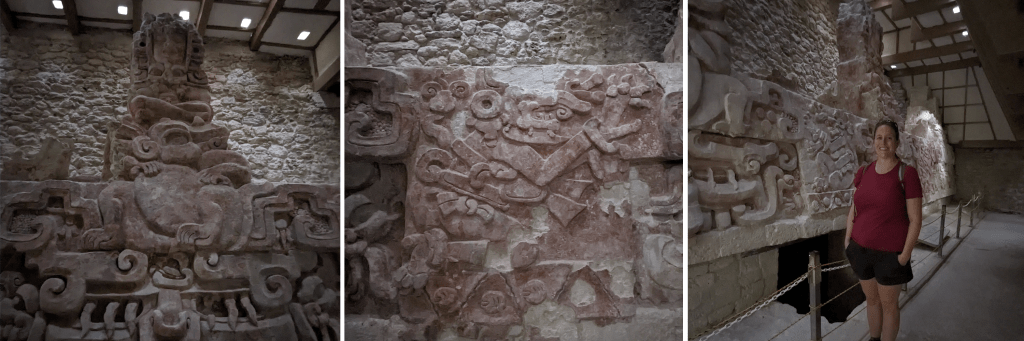

Valladolid is home to the former Convent of San Bernardino de Siena, which was home to a Franciscan order of friars. This confused me for a bit, because in contemporary English, convents generally are for nuns. However, apparently back in the day, the word convent was less gender-specific.

The outside of this building has a fun light show that tells the history of Valladolid every night, which includes the city’s role in the Caste War. In New Spain, there was a clear caste system with white Spanish (criollos) at the top, mixed indigenous and European ancestry (mestizo), the descendants of indigenous people who had helped the Spanish to conquer the Yucatan, and then other native groups and African slaves at the bottom. In an earlier post about Mérida, I discussed how the city became super rich from growing henequen. There were henequen haciendas all over the peninsula and the mostly white and mestizo Mexicans were getting rich, while indigenous Mayans were forced off their lands and then made pennies growing and harvesting the henequen for the owners of the estates.

As land continued to be privatized, Mayans organized to prevent their communal land from being taken by outsiders. One of the first events of the war, in 1847, occurred when Mayan soldiers in Valladolid rebelled by sacking and destroying the city. Inside the well located within the convent’s walls, archaeologists have pulled out rifles, bayonets, spears, and a cannon, all dating from the conflict from this time period.

The resistance was actually mostly centralized on the eastern coast of the Yucatan, south of Tulum. They declared themselves as a free state and, for a while, had extensive support of arms and trade from the United Kingdom. Also important to the war effort was the emergence of a Mayan religion that incorporated elements of Christianity and was inspired by a Talking Cross at a cenote. This church (sometimes known as the Cult of the Talking Cross) played a critical role in supporting the resistance. The uprising officially ended in 1901 when the last group of Mayan rebels were defeated.

former Convent of San Bernardino de Siena

courtyard, main church, view upwards of a peace dove from the pulpit (which I found incredibly ironic given the Catholic Church’s involvement in wars and genocides around the world)

One of my favorite places in Valladolid was Xpokek, a small local apiary that gave bee tours. Mayans have always had a close relationship with bees and pre-European contact, native bees were kept inside logs where they built elaborate hives. To harvest the honey, the logs were split open and the bees were moved into a new log. Bees were central to Mayan life and the Mayan god of bees and honey was Ah Muzen Cab (maybe the same upside down god on the Tulum ruins). The native melipona bee is stingless and makes a relatively small amount of honey, only about three pounds of honey per year. In contrast, European honeybees make twenty times as much honey. Melipona honey is rarely eaten and instead is used as a treatment for cataracts and to prevent bacterial treatments in wounds. I also got to eat sikil pak for the first time there, which is a Mayan dip made of pepitas (pumpkin seeds), charred tomatoes, and spices. I’ll definitely be making this after I leave Mexico.

sikil pak, Mayan dancers in the central park in Valladolid, Melipona bee guarding the entrance to their log hive

I did mention the great food, right? Tepache is a kombucha-like fermented drink made out of the rind of pineapples, probably first made by the Nahua of central Mexico. Papadzules are egg stuffed enchiladas covered in a sauce made of ground up pumpkin seeds and a well-loved Yucatecan dish. Tejate is Oaxacan in origin and made from maize, cacao, and the pits of the mamey fruit.

tepache, papadzules, tejate

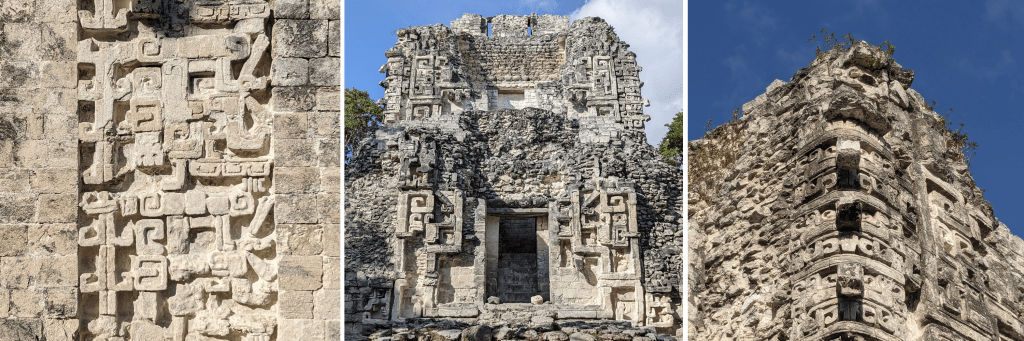

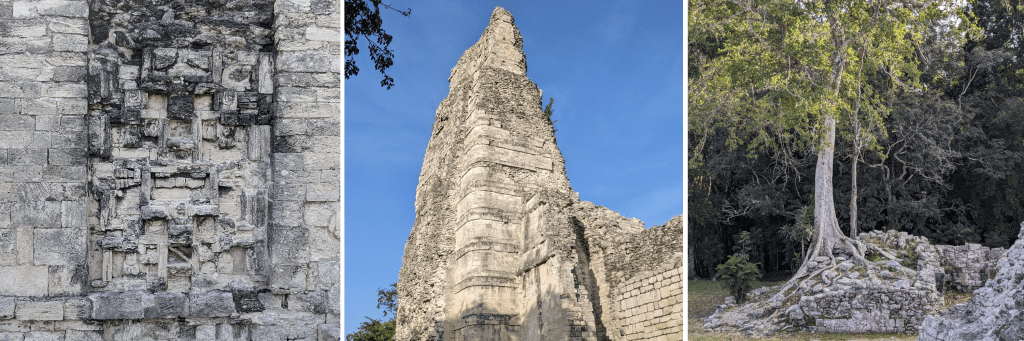

Campeche

I was struggling in the heat of Mérida, so I took a journey to the western side of the Yucatan peninsula. Mostly I went because I wanted to see the jade mask from Calakmul, but ended up having a lovely weekend in this heavily fortified old city. The walls built by the Spanish still surround the old city, and even though it is located on the Gulf of Mexico, there are no beaches or places for locals to enter the water. However, the malécon along the water’s edge makes for a lovely stroll. Today, Campeche is known for its streets full of colorful houses, which are a joy to wander through.

Back in the day, Campeche was well-known for a type of wood called palo de Campeche, which was used to dye cloth a variety of colors, including brown, purple and orange. This is because it changes color based on its pH. This wood was one of prizes pirates would take from cargo holds when they commandeered ships in the area. Campeche was known as one of the cities where pirates would hang out in between their raids.

view along the malécon, nighttime fountain show, view from the old fort

The old fort is home to a regional museum holding lots of Mayan treasures. Many of the pyramids and ruins in Campeche state have been excavated and brought to this museum. In addition to all of the fancy jade masks, I thought this burial outfit and funeral carpet were exquisitely constructed. The amount of work required to make and sew all of the shells and seeds is unfathomable to me.

collar made of snail shells covered in cinnabar to give the red color, close ups of a funeral carpet made of shells and seeds

When I was in Chile a few years ago I ate a brazo de reina (queen’s arm) which was a sweet dulce de leche filled roll. However, here in the Yucatan, a brazo de reina is a hard boiled egg-filled tamale. The other really fun food speciality in Campeche was a machacado. The bottom of a cup is filled with mashed up fruit of your choice, covered in shaved ice, and then topped with condensed milk, more ice, and a bit of cinnamon. It’s a lot of sugar, but definitely a regional treat adapted for the heat.

Yucatecan brazo de reina, cute llama stamp on napkins, mango machacado