Leaving Bhutan

Many weeks have passed, but I wrote this the day I left Bhutan: One of the things travel does for me is that it reawakes my sensitivities to the world around me. I arrived in Bhutan, jet-lagged and tired from two days of long travel and I remember looking out the window from the car from the airport. Everything was new to my eyes. Prayer flags everywhere. Intricate wooden construction of houses, painted in meticulous detail. I remember thinking everything was beautiful, but also everything was so different from everything I know and understand.

Although it has only been two weeks, I’m leaving and the leaving is also tainted with sadness. The buildings no longer look strange. The prayer flags blend into the background of every scene. The things that once stirred me to wonder are just a part of the world I’m in. And I think that’s what brings the sadness – the leaving of comfort, the leaving of familiarity, the leaving of kindness and friendship of people who I still barely know.

It’s always a weird feeling to be going off on my own again.

Entering India

It was immediately apparent that I was no longer in Bhutan. That atmosphere had changed completely. Calm, chill, peaceful, green. Chaos, trash, noise, city. I was joking with our driver that he hadn’t used the horn in four hours of driving in Bhutan, but had used it three times just getting from the border to our parking spot in India. He definitely possessed bicultural driving skills.

My guide Tenzin got me through all the border shenanigans of stamped paperwork. He had gone to school in Darjeeling and was chatting away in Hindi with all the border guards. In addition to Dzongkha, he speaks a local dialect of the language used in his village near Trongsa, Hindi, and English.

Before finding me a taxi to my next stop, we all went out to get lunch. On the way, a bunch of cattle came sauntering down the street. Tenzin practically tackled me to make sure I didn’t get run over. Another few cattle came by and although they weren’t moving so fast, one of them swung their poop-covered tail in my direction leaving a giant brown mark across my shirt and my right hand. Our driver was similarly splattered. Welcome to India.

I cleaned myself up at the restaurant and had a lovely meal of masala dosa before being packaged into a taxi and sent on my way to Jaldapara National Park, located a mere hour away from the border crossing. Once out of the border city of Jaigaon, the honking and general noise gave way to acres of tea plantations and relative calm.

Jaldapara National Park

Even a couple weeks before we started the trip, my post-Bhutan plans kept changing. Originally, we were going to leave through the border on the eastern side of Bhutan into India. Our tour agency thought that border might open up by the time we got there, but it was still closed. This meant we needed to do a massive reroute ending up back in Paro at the end of our trip. I had a week of free time and had originally planned on going to see Indian rhinoceroses in Assam province. Trying to formulate I new plan, I pulled up Google Maps and just started looking around to see what was near the western border crossing with India. Lo and behold, there was a national park nearby that also had rhinoceroses!

And that is how I ended up in Jaldapara National Park. This is definitely a local tourist destination for families. People drive in from nearby cities to get a taste of nature. The park itself has a couple of lodges, so I was able to stay right inside the front gate after negotiating what can only be described as Indian government technological bureaucracy. There were so many online hoops to jump through for no reason at all. Regardless, I made it to the park and the nice guy at the front desk helped me book a safari for that evening with another family.

me and Tenzin and our dosas, Indian peafowl, gaur

The safaris are touted as gypsy safaris, which was super confusing to me at first, especially because that’s a term that is now considered a racial slur of the Roma people. Although Romani are often associated with living nomadically in Europe, according to genetic research, they were most likely originally from Northern India and left about 1000 years ago. Their original caste name in Sanksrit was Doma, which referred to a people who made their living by singing and playing music. That made them dalits, low-caste untouchables without many rights and privileges afforded to members of higher castes. Although many of the laws segregating Indian society into castes have gone away, socially the caste system and discrimination caused by it is still very real.

With some more research, I found out that the term gypsy refers to the Maruti Suzuki Gypsy, which was a four-wheel drive vehicle that was very popular with the Indian army and police. They are no longer manufactured for the general public, but Suzuki still continues to make them for the army. I tried to find out why Suzuki named the cars gypsies, but there wasn’t much about their origin story online.

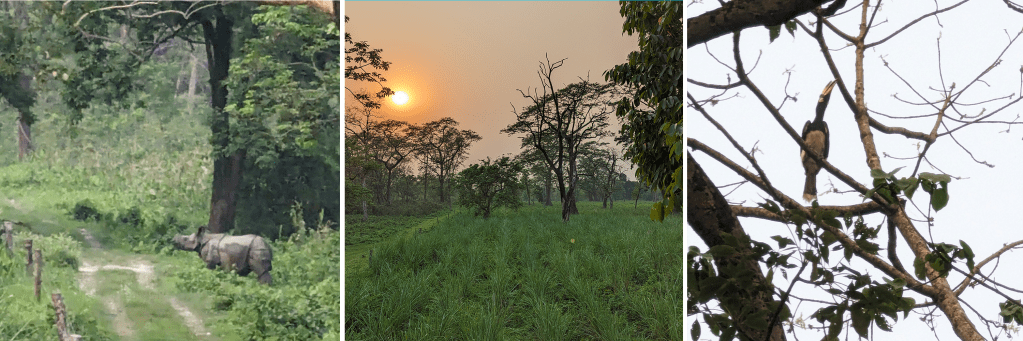

The cars can hold up to six people in the back and have a driver and guide in the front pointing out different flora and fauna along the way. I went on one tour at sunset and another one at sunrise, and ended up seeing a lot more during the evening tour. We did see one Indian rhinoceros from very far away. My phone has 30x zoom on it, or all I would’ve see was a blurry gray blob. I did manage to see an Indochinese roller, which reminded me so much of the lilac-breasted roller that I saw on safari in Tanzania and Zimbabwe. All of the rollers have such magnificent colored feathers. I think if you wanted to turn someone into a birder, you should get them watching rollers in the wild. Just stunning. I’m also a fan of the hornbill, with its fun calls and strange looking beak.

gypsy vehicle, Asian house gecko in my room (top middle), Indochinese roller (bottom middle), wild boar

Indian rhinoceros, planted fields, Oriental pied hornbill

Probably one of the most amazing moments was when we went to the Hollong Tourist Lodge. In front of this place, they’ve set up salt licks, which are basically giant blocks of salt that the animals come and lick. During the evening tour, a giant herd of elephants came to visit through the trees and we stayed for a long time just watching their slow and steady movements.

sambar, Asian elephants, Eastern cattle egrets

As part of the evening tour, young women of the Bodo (or Boro) tribes performed some traditional dances. The Boro people are traditionally from Meghalaya and Assam province and were originally part of a large number of different tribes that slowly merged into one larger identity. From my very brief research, the early Boro leaders and elites seemed to have created an existence for themselves outside of the Hindu caste system, by defining their caste as Boro on census reports. They still have control of the autonomous region of Bodoland in Assam to this day. Because of our elephant watching our group actually arrived a bit late, but I did get to capture this catchy music and dance performance that highlights their fishing traditions.